Supporting a child with auditory processing disorder

- Autability

- Sep 8, 2025

- 4 min read

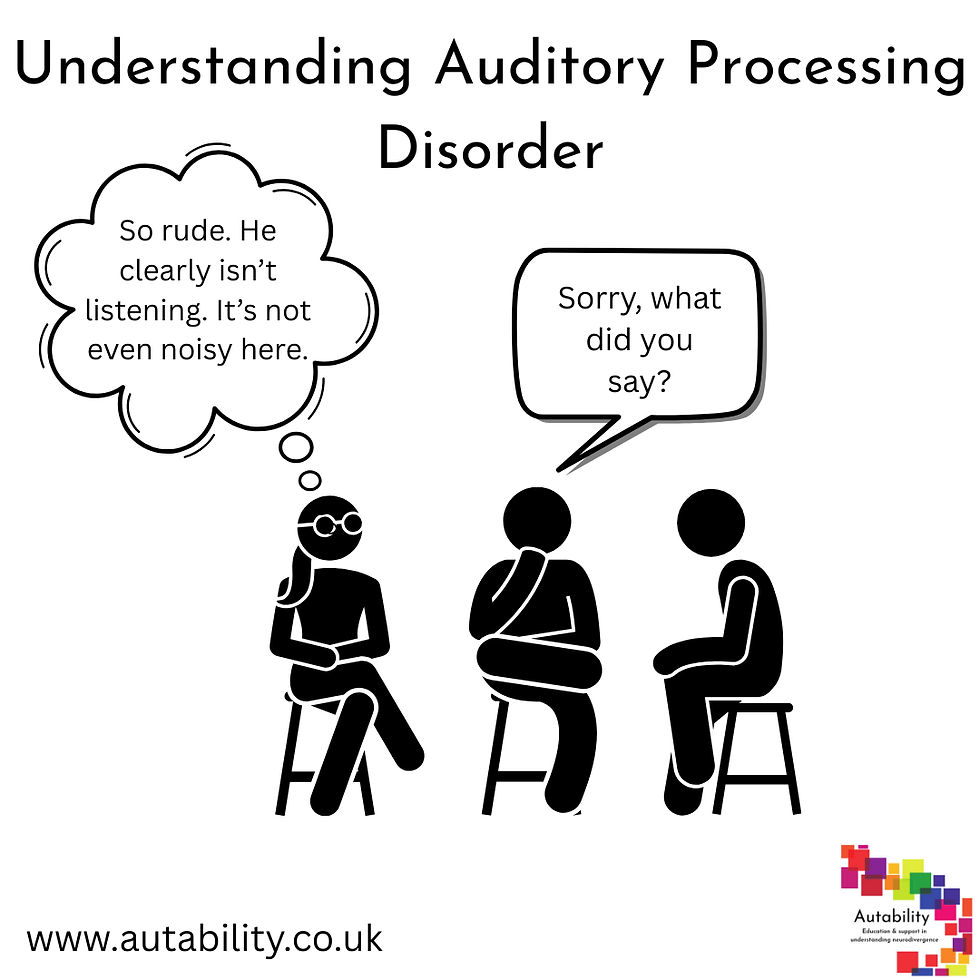

When your child struggles to understand spoken instructions, everyday life can feel like a constant uphill battle, not just for them, but for you as well. It’s not about whether they hear you. In many cases, the ears are working just fine. What they’re struggling with is what’s known as auditory processing disorder (or APD for short).

With APD, the brain has difficulty making sense of the sounds it hears. So, even though everything is getting in, it might not be getting processed clearly. It can feel a bit like someone’s trying to tune in to a radio station but can’t quite get the signal. Background noise, unfamiliar voices, or rushed speech can make it ten times harder for that information to land.

At first, this can look like a child who’s not listening, not trying, or being deliberately difficult. But in reality, many children with APD are working incredibly hard just to keep up and often getting exhausted in the process. The good news is, there are things we can do that make a real difference. These might feel small, but they often lead to calmer, more successful days.

One thing that helps straight away is making sure they’re actually ready to listen before you speak. We often assume kids are tuned in just because we’re ready to talk. But if they’re mid-task, mid-thought, or somewhere else entirely in their head, your words might not land. We’ve found it helps to say their name, gently touch their shoulder, or wait until they look up. That moment of connection can make all the difference.

When it comes to instructions, less is more. Avoid saying things like, “Go upstairs, brush your teeth, get your pyjamas on and bring your clothes down for the wash,” and then wonder why only one of those things happened. Keep it simple: “Go and brush your teeth. Come back when you’ve done that.” Then we give the next step. Yes, it takes longer. But it works, and there’s less stress all round.

Another big help has been adding visual support. That doesn’t mean fancy laminated cards (unless that’s your thing). Sometimes it’s just pointing, using your hands, writing a little checklist, or drawing a stick figure plan on the back of an envelope. Many kids with auditory processing challenges are visual thinkers. Seeing the information as well as hearing it gives their brain another route to understanding it.

If something hasn’t landed the first time, it’s easy to fall into the trap of repeating it louder – we’ve all done it. But louder doesn’t make it clearer. The problem is usually the wording or the speed, not the volume. Try rephrasing. Swap “Hurry up, we’re going to be late!” for “Shoes on, please, we’re nearly ready to go.” You’ll often see the lightbulb switch on when you find the version that makes sense to them.

We’ve also learned the value of keeping language and routines consistent. Using the same phrases for the same tasks helps reduce the effort it takes for a child to process what’s being said. Saying “Toothbrush time” every evening might sound repetitive to us, but for them, it creates a sense of safety and familiarity. The predictability makes things easier.

And perhaps most importantly, we try to validate what they’re experiencing. If they say they didn’t hear or didn’t understand, we believe them. We don’t say, “You were standing right there!” or “How many times have I told you?” – even though yes, it’s frustrating. Instead, we try to say things like, “That was a lot at once, wasn’t it?” or “Thanks for letting me know, let’s try it another way.” Those moments of understanding build trust, and that trust helps them feel safe enough to ask for help next time.

In school settings, auditory processing difficulties often get misinterpreted as behavioural problems. Children might seem distracted, disengaged or even defiant, but the truth is often more complicated. A child might do really well one-on-one, but struggle in a group. They might follow written instructions perfectly, but miss verbal ones completely. They may seem fine in the morning but unravel by the afternoon, simply because their brain is worn out from working so hard to decode the day.

One teacher once told us they didn’t understand why our son was covering his ears – “The room wasn’t even that loud.” But to him, it was. A ticking clock, a humming light, scraping chairs, overlapping voices – all of it can build up until their system just can’t cope. What sounds ‘quiet’ to us isn’t always quiet for them.

So, what helps? Start by writing things down. Jot down the times of day when things go better or worse, the settings that cause stress, the strategies that seem to help, and the patterns you notice. These notes can be so useful when talking to teachers or professionals. And even if there’s no formal diagnosis yet, they help you better understand your child.

We’re not going to get it right every time. None of this is about perfect parenting or teaching. It’s about making enough small changes to help a child feel heard, understood, and capable. Because they are capable, we just need to give their brain the space and support it needs to do things its way.

They’re not being difficult. They’re navigating the world with a brain that processes sound differently. And with the right support, that world gets just a little bit easier to manage.

.png)

Comments